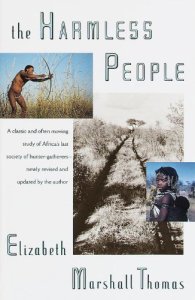

By Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. 1989.

Note: This book chronicles the experiences and observations of the author when she first encountered the !Kung Bushmen in the 1959. This second edition was published in 1989, thirty years later. By that time, conditions had changed profoundly, for the worse. See her epilogue for the discouraging details.

Chapter 3: The Bushmen

We gave them some more tobacco as a gesture of our good faith and we told them that we had come from America, hundreds of days’ travel and across a great body of water, but of course they had never heard of America or the ocean and thought we mean the Okovango River, and at that they didn’t really believe us, although they were too polite to tell us so.

Chapter 4: The Fire

As we walked, fine black powder rose to dust our legs, and now and then, off through the standing tree trunks and between the fallen trees’ great upflung roots, little whirlwinds crossed back and forth, raising the dust in spiraled pillars. Bushmen say that whirlwinds show the presence of the spirits of the dead.

In that band there were six men, five of them in their thirties, five women who seemed very much younger, and one woman who was very old. There were also three young boys and three babies, two girls and a boy. We guessed from the looks of the people–and later found that we were right–that the band was a small extended family.

Epilogue: The Bushmen in 1989

The fate of the group of Gikwe Bushmen in Botswana (then the Bechuanaland Protectorate) shows what has already happened to many southern African Bushman and what, for others, may be still to come.

The concept of Bushmen in a faraway wilderness, pleasant as we may find it, is simply and perniciously untrue. No Bushmen lack contact with the West and none is undamaged by it. and their own way of life, the old way, a way of life which preceded the human species, no longer exists but is gone from the face of the earth at enormous cost to the individuals who once lived it.

As the money economy displaced the old hunter-gatherer economy, it displaced the social usefulness of nearly everybody. By hunting, the men had once provided much-needed, highly valued protein food as well as the other animal products used for implements and clothing. By wage-work, the men provided a few coins which bought nothing in adequate amounts. By gathering, the women had often provided all the food for everybody, and at least had provided for themselves and their children. In the new economy, they provided nothing. The old people once had minded the children and made the clothing. In the new economy those services weren’t needed. The old people also were the repository of information that might sometime serve the young. This stored information is hard for literate people to imagine, and its use is seldom witnessed. Nevertheless, it is there and can be lifesaving. For example, if serious weather conditions occur every fifty years or so, only the old people will remember the last occurence and the tricks which were used to survive it. In fact, while I was there I saw a man in his forties make an error in tracking which his father, alive but not present, would have corrected. But in the new economy, not evenm the old memories were useful, since they did not apply to the new away of life. The old people became burdensome. The number of old people in the population has dwindled as seriously as the number of small children.

But after a few years of living in the government’s housing projects of tin-roofed, one-room concrete huts, damp, crowded, and without sanitation, they were getting the diseases of overcrowding and poverty–tuberculosis, typhoid , meningitis, measles, venereal diseases, and many others–with tuberculosis and the various kinds of diarrhea being the most pernicious and destructive, especially to small children.

And the diet was poor. the old diet of wild foods had been nutritious enough to sustain our ancestors for three million years. Not so the diet of posho or mealie-meal, the cornmeal porridge which eventually became part of or purchased by the workers’ pay.

For another thing, many Bushmen were now ashamed to eat veld food (if any could be found). The stigmata of eating food taken off the ground, of picking food up out of the dirt, of having to go searching for food in wild places like an animal, of having no supply of food, no firm idea where a meal would come from, were by now deeply felt by the Bushmen, and were why many people (themselves included) didn’t use the term “San.” They were why Bushman people willingly bought expensive store food as well as transistor radios, ghetto blasters, ballpoint pens. To own such items, as the rest of us demonstrate so abundantly, was to rise in Western civilization–from the lowest, meanest edge where the bushmen by then clung.

The picture of Tsumkwe would not be complete without a fundamentalist Christian church to decry the depravity–the drinking and the fighting–and sure enough, Christianity cam with its optimistic message that the Higher Powers if the white people care about the goings-on. If only because the sermons were in Afrikaans, Bushmen didn’t rush to conversion.

Perhaps not surprisingly, yet dealing a final blow to the loss of control over social tensions, people stopped the n/um chai, or medicine dancing.

Thus ended the old ways. The Bushmen had learned that they were the scum of the earth, the poorest of the poor, that they lived in the meanest of houses, that the dogs owned by the whites at Tsumkwe were far more valued and much better fed. The Bushmen had found out that they were unskilled, despised, deemed lazy, ridiculous, and dirty. They had learned how the outside world saw them.

And they agreed. Their honor was lost–their culture, too. Whole families who once were able to feed and clothe themselves, once able to depend upon one another, became completely dependent on one family member–perhaps a young member, a teenage soldier, say, who had learned his values and priorities in the barracks.

Many people under thirty hardly remembered the old way of life. Others remembered but had forgotten the skills necessary to lead it. Even people in their forties who knew some of the skills lacked the fine knowledge that everyone once had. Only the old people remembered everything, and it was they who best realized what had been lost.

“Among contemporary !Kung San,” writes Edward O. Wilson, “violence in adults is almost unknown; Elizabeth Marshall Thomas has correctly named them the ‘harmless people.’ But as recently as fifty years ago, when these ‘Bushman’ populations were denser and less rigidly controlled by the central government, their homicide rate per capita equalled that of Detroit and Houston.” (On Human Nature, Cambridge, 1978, p.100)

As Jamie Uys in his film, The Gods Must Be Crazy, misrepresents the Bushmen, E. O. Wilson reverses their history. To my knowledge, E.O. Wilson has never visited the Ju/wasi. His book never mentions how important it was to them to keep their social balance, how carefully they treated this balance, and how successful they were. That he discusses them at all is perhaps due to the fact that in the 1970s they were selected by academics as a sort of living laboratory in which studies could be made on attributes of human nature, the most intriguing of which at the time seemed to be aggression. As it is discouraging that Uys, in a film viewed by millions, exploits the myth of precontact Bushmen when the truth is so horribly different, it is discouraging that an academic as eminent as Wilson thinks that “control by the central government” gave Ju/wasi their social equilibrium. (p.283)

When our family first went to the Kalahari, we realized that we were visiting a unique people who, living as hunter-gatherers, perhaps were living as our preagricultural ancestors may once have lived. (p.283)

In Namibia in the 1950s, we found people anxious to suppress their aggression. This seemed to be in contrast with the findings of the anthropologists in Botswana, where people seemed willing to express aggression. That differences were found between the two groups of Bushmen did not surprise us, for the Botswana studies were begun many years after ours, in another country, among different people living under very different conditions. How different can be seen from Marjorie Shostak’s fine book, Nisa: the Life and Words of a !Kung Woman (Cambridge, 1981), which resulted from her work there.

What did surprise us was that the Botswana anthropologists sometimes suggest that the differences are due to personal predilections of the investigators, as if Bushman groups everywhere uniformly display, so to speak, a finite amount of aggression which our investigations overlooked but which the anthropologists in Botswana discovered. I wish I knew who first explained that anthropology now suffers from physics envy.

In consequence, from time to time the suggestion arises that we didn’t really see what we say we saw. Shostak herself, and her husband, Melvin Konner, write as follows: “Briefly stated, the !Kung have also been called upon to remind us of Shangri-La [sic]. While they were spared the attribution of free love that came rather easily to the minds of observers in the South Seas, they have received considerable attention for other alleged characteristics that also drew attention to Samoa. These included a relative absence of violence, including both interpersonal and intergroup violence; a corresponding absence of physical punishment for children,; a low level of competition in all realms of life; and a relative material abundance. In addition to these features that the !Kung and Samoan utopias seemed to have in common, the !Kung were described as having exceptional political and economic equality, particularly in relations between men and women.”